Still, between those, and "Lincoln" (150 minutes), "Skyfall" (143 minutes), "Les Misérables" (158 minutes), "Zero Dark Thirty" (160 minutes) and "Django Unchained" (movie still running), filmmakers seemed to argue that if less is more, think about how much more more would be. Presented are 10 movies, in alphabetical order, that find greatness while still maxing out at one REM cycle. Take note, Hollywood. All of your ideas for a movie aren't worthy simply because they exist.

BEFORE SUNSET (80 minutes)

This movie flows. It glides. And it all seems effortless. Presented entirely in real time, director Richard Linklater and his cast of two deliver remarkably fluid dialogue that begins with pleasantries and gradually, believably breaks down to the characters' realizations that little in their lives went according to plan. Between this movie and "Before Sunrise," Linklater displays a keen eye for those brief, random moments that forever change your life.

BICYCLE THIEVES (89 minutes)

Italian neorealism takes cinema that was crushed into rubble and builds it anew with what's left. A man has a wife and son who would look sad even with a smile. His job requires one thing - a bicycle. His bicycle is stolen. He tries and fails to recover it. This film, probably the neorealism's crowning achievement, breaks your heart over and over again so many times, thank god it's not an epic. Its deep, unimpeachable sadness cuts to your core.

DETOUR (68 minutes)

You want real film noir? The seedy, lurid soul of a genre about characters whose souls just sucked, plain and simple? Here it is - everything about noir you want, and nothing else. Shot on the cheap, the movie lacks everything a conventional film class would tell you a movie "needs." But that grimy lack of production values plays up the film's wasted heart, and it has attitude to spare. Most movies on this list are short by choice. This is probably the only one that is short simply because they couldn't afford more film.

DUMBO (64 minutes)

A bit of a cheat, sure. Early animation's painstaking production process required the movies to be short by design, lest the staff garner intense carpal tunnel. Still, good storytelling is good storytelling. My favorite of Disney's WWII era features, "Dumbo" zips from beginning to end, zipping in a zippy way. There's simply no time to be bored. Plus, my mother still cries at the "Baby Mine" sequence. For whatever that's worth.

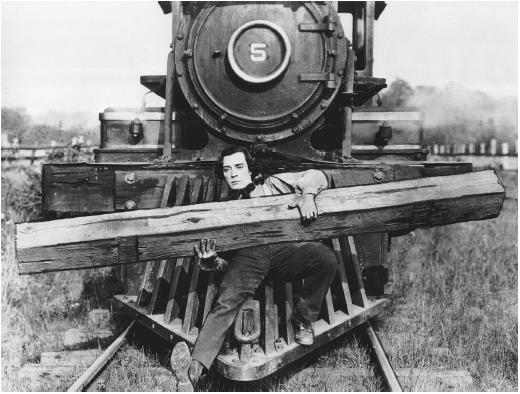

THE GENERAL (75 minutes)

About 75% of what I think is funny, I'd wager, comes from Buster Keaton. Funny isn't people trying to be silly. It's people trying to be serious and failing. "The General" finds Keaton at the peak of his powers, a man desperately clinging to his dignity as everything crashes down around him - if Chaplin was the Spielberg of his day, Keaton was the Wes Anderson, offering straight faced characters unaware of the insanity in the background.

KILLER OF SHEEP (83 minutes)

How did this movie go undiscovered for so long? And what a crime that is. A kind of weird fusion of Altman, Kubrick, De Sica, and Cassavetes, Charles Burnett's short little masterpiece is like as science experiment gone horribly right. Shot in 1979, it set on the shelf for almost 30 years, but now it's finally getting its due. With no discernible story, arcs, or meaning, Burnett's vignettes of working class life in Los Angeles' Watts district just teems with life itself.

PATHS OF GLORY (88 minutes)

Kubrick had a heart. He just by and large didn't feel like using it. One of the few exceptions, though, being this 1957 anti-war tale of a French WWI officer who refused to carry out a suicide mission and defended his men against accusations of cowardice in court. Kubrick's classic "2001" and "Dr. Strangelove" both depict machinery acting exactly as designed and bringing on chaos. Similar to a theme explored in this earlier work, except the machinery is war. Such a moving story, told is such economy.

PICKPOCKET (76 minutes)

Christ, if only every movie told their stories with such laser precision as this one. To bust out an old trope, this movie works like a samurai - enters the room, does its job, and leaves not a moment too soon. Every shot matters. Every cut matters. Director Robert Bresson reportedly shot takes over and over again until all soul drained from his actors' faces, wanting a movie that offers no emotional cues. Here is a movie that isn't short as much as it's exactly as long as it has to be.

RASHOMON (88 minutes)

If "Rashomon" didn't exist, it would be necessary to invent it. The movie speaks to such a fundamental aspect of human nature, that the "Rashomon Effect" entered the public lexicon simply because there was no better way to describe it. No great secret to say that people lie. Kurosawa takes it a step farther, though, and suggests these lies really aren't lies when the tellers all believe it. Basically, factual events are subjective and nothing is knowable. Such an idea has no answers, and thus no need for the movie to drag. There it is.

STAND BY ME (88 minutes)

Stephen King crowns this the best adaptation of his work, and although time will tell on "Dreamcatcher," I get where he's coming from. A coming of age story of four boys blissfully unaware of the cold hard punch of life waiting for them around the corner, this movie is so light and gee-whiz charming without being cloying about it, you forget its about people trying to see a dead body. What a little treasure of the movies. Make more stuff like this, Rob Reiner! We miss you.