THE BABADOOK (directed by Jennifer Kent, 2014)

Describing what made Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining" such a crown jewel of horror, Steven Spielberg once pointed to the classic "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" scene. Shelley Duvall discovers Jack Nicholson's ramblings, shedding page after page from her trembling hands, as the music swells and we instinctively know, thanks to the cliches of horror, that someone's gonna pounce.

A lesser director, Spielberg said, might go for the easy scare. Jack leaps from around the corner, piano chord crashes, audience's popcorn flies, and we move on. Kubrick instead took the subtler approach, shifting the camera to Jack's perspective as he sneaks behind her and we're right there with him. This robs us of the jolt moment, but it also builds a quieter, more effective terror. The kind of terror that finds a home in our marrow and comes out to taunt us when we're lying alone in bed at night.

That thought stuck with me while watching "The Babadook," writer/director Jennifer Kent's masterful new work of horror. Those hoping for quick jumps in their seats need not enter here. That's not terror. That's the release, and it wears off like a carnival joy buzzer. Kent knows that what burrows under your skin is the build, the anticipation, the knowledge that something is around the corner and you can't do anything about it.

She also taps into the primal understanding that having kids can be a scary friggin thing.

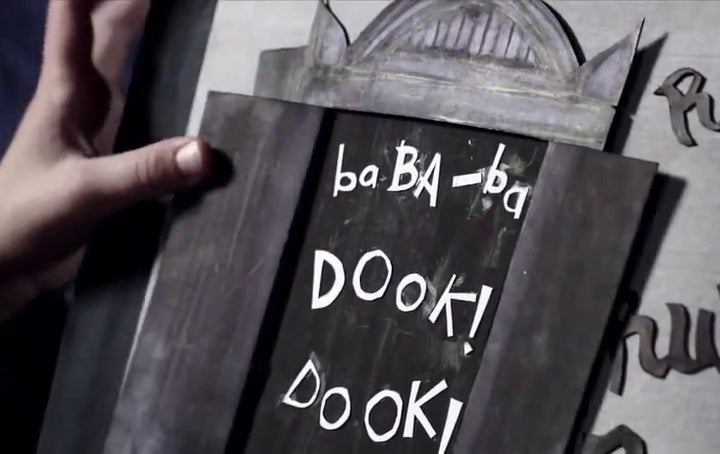

"The Babadook" sprouts from a haunt as basic and elemental as The Boogeyman. Amelia (Essie Davis), a widowed mother, finds raising her young son Sam (Noah Wiseman) alone to be a touch, shall we say, difficult. He doesn't socialize well with other children. He never behaves. Now he brings home a picture book that reads like Maurice Sendak actively wanting to send kids to therapy - a book about a mysterious creature called The Babadook - and believes this creature to be haunting their house. Amelia naturally assumes this to be Sam typically acting out, until a few incidents slowly force her to reconsider.

Think "We Need To Talk About Kevin" meets "The Conjuring," and you're on the right track.

To understand what makes "The Babadook" such a singularly effective hair raiser, lets go where even the best horror flicks can stumble: the last act. That point where fun and games are over, and it's time to wrap things up. What this unfortunately means is the suggested often must become literal, and it loses some punch. By the time we see the mother's chair doing silly flips at the end of "The Conjuring," it's kinda tough to be invested. Kent ingeniously bypasses this in "The Babadook" by making the haunting itself entirely suggestion. For every horror setpiece sequence in the movie, she never shows her hand. Each appearance of the Babadook defies easy categorization, cleverly framed and edited by Kent so that it could just as easily be a product of the family's imaginations as the real deal.

Some of the more mixed reviews point to this as a cheat. Once we accept that the Babadook may in fact be imagined by Sam and Amelia, what's there to be afraid of? And yet, isn't that what's to be afraid of most? Maybe the Babadook is real. Maybe it isn't. That's your prerogative. The effects are certainly real, though. The family's resulting screams and panic and breathless dives beneath the covers are all there. Now take that and think about the one base fear that drives everything from hot teenagers getting hacked by Leatherface to the classic dream where someone chases you, but your legs can't move: inability to escape.

Making the Babadook a real thing makes it something we can theoretically understand, but it also becomes a thing we can theoretically defeat. Keeping it a figment of Sam and Amelia's imaginations, though? There ain't no escape from your own mind.

So strip away the perceived haunting from the surface, and whatta we got? What do the events of "The Babadook" look like from the

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern perspective? Why, something that strikes the heart of the child in all of us: a mother who hates her son and wants him dead. A mother who has had enough, who isn't a source of protection and safety anymore. And, for the parents out there, the idea that your one sacred charge on this earth - protect your offspring at all costs - can be brushed aside in favor of your most horrible instincts.

If there's one thing scarier than a monster in your house trying to kill you, it's the idea that you can't run to your own mother.

What an exercise in precise control "The Babadook" is. Anchored by two impeccable, intense performances from Davis and Wiseman that never quite let us know where we stand, it's less concerned about what goes bump in the night than the fact that what goes bump ain't going anywhere. And as a filmmaker, Kent allows her scares to build from within, starting with honestly realized characters and growing organically from there.

Your popcorn won't go flying. You'll remain still in your seat. But good luck conceiving tonight, folks.

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

Best Scene Of 2014: The Finale Of WHIPLASH

(WARNING: Major spoilers ahead for "Whiplash," if that's not quite your tempo)

One of the most obvious, and yet fundamental, questions we must ask when watching a movie is, "What is this about?". What's Robert Altman's purpose in tracking two dozen seemingly random strangers for a few days in "Nashville"? What's Martin Scorsese getting at with this weirdo in "Taxi Driver?" Such a basic question centers us, reframes the movie, and then allows us to judge whether or not it was a success based on the answer.

So what, then, of "Whiplash," one of 2014's most searing works? Is it a maniacal twist on the classic 1980s Tom Cruise formula (young hotshot upstart crosses paths with an aged mentor who pushes him to new heights)? A morality tale of the lengths one must travel to be a great artist - not just good, but great - and whether it's worth wrecking your life over? Or simply, as my friend Isaac Weeks put it, a platonic hetero love story of two insane assholes?

Maybe you agree with any of those statements. Maybe you think "Whiplash" is a parable for the Kennedy assassination for all I know. My purpose at this free movie blog isn't to say you're wrong - not today. Instead it's to say that "Whiplash" writer Damien Chazelle doesn't think you are either. His movie remains a tense, volatile high wire act throughout, quietly intelligent with nary a speck of braggadocio, and sporting two of the best performances of the year from Miles Teller and JK Simmons. Chazelle, like any artist whose confidence matches his brains, trusts the audience to be on his level and to not require a trail of bread crumbs to follow along. Masterful storytelling from the word go.

Then the finale. My god, the finale. Lets get the surface out of the way - did 2014 yield a tenser, more explosive five minutes of film? For that matter, was it even five? Maybe it was 20. Maybe it was one. I honestly don't know. Time seemed to vanish. By this point, young wannabe jazz drummer Andrew (Teller) has turned his nearly destroyed life upside down to earn the satisfaction and tutelage of famed, vicious music instructor Terence Fletcher (Simmons), who seems to model himself more after R. Lee Ermey than Mr. Holland and his opus. Fletcher, who repeats the story of how Charlie Parker became Bird like he tells it to himself at night to sleep, comes from the notion that any amount of abuse flung toward the young musicians he conducts, be it verbal, physical, or emotional, is worth it if it pushes even a single person to become that one great artist for the ages.

Fletcher wants to find that one great artist (an earlier scene of him playing piano competently but unremarkably at a jazz club suggests an inner frustration at not being that person himself). Andrew, who sheds blood on his drum skins to the point where you question how he remains conscious, believes himself to be that one great artist. He endures every bit of torment Fletcher hurls his way, all for the chance to prove himself. Now, with Fletcher in need of a substitute drummer for a JVC festival concert at Carnegie Hall, Andrew finally has that chance.

One thing worth nothing, before we go any farther - these two men are major jerks. I don't mean the type that you can understand and even respect for their grander ambitions. I mean they're two extreme, wouldn't-want-to-spend-five-minutes-alone-with-them pieces of shit. Fletcher quite literally ruins lives (it's strongly implied his methods drove at least one former student to suicide). Andrew coldly casts aside everyone who cares about him - father, girlfriend - for the sake of his shot at artistic eternity.

I make this point because a lesser movie might play the finale, with Andrew finally proving himself a worth drummer to Fletcher, as a stereotypically rousing finish, maybe even complete with that one person Andrew didn't think would make it arriving at the last second. Instead, emotional stakes for both men firmly established, Chazelle stages it like a friggin mushroom cloud. Andrew doesn't so much drum as he seismically erupts, wailing down his sticks like he's piloting the Enola Gay, as the scene goes on...and on...and on...escalating to an armrest gripping degree.

This isn't an emotional release. This is an emotional assault, one that Chazelle captures in a series of increased close-ups on these two men as the audience and even the other band members on stage vanish from the frame. The background seems to go black behind them. All other noises besides Andrew's drumming and Fletcher's directions dissipate. We know, on the surface, that this final sequence is of Andrew's ascendance to the realm of the greats. But our feeling isn't one of pride or hope or joy. It's sheer, tense terror. Not so much, "Yay, these two men found each other," as, "Oh no, these two men found each other."

Who knew the most agonizing, thrilling sequence of the year would revolve around a young man drumming more than he's supposed to and an older man wanting him to stop until he wants him to keep going? And my earlier point regarding what "Whiplash" is about? Your answer to that informs how you see the finale. But one of the great little cinematic magic tricks this year is that the movie could end on such a deeply satisfying note while at the same time allowing all views to remain valid.

There's so many ways Chazelle coulda ended "Whiplash" well. He picked the one that ended it great.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)